The Busy Person's Guide to Building Technical Data Science Skills (in Six Steps)

Learning data science can change your life.

Five years ago, I was working full-time on a salary that paid the bills and not much more. Now, I’ve more than tripled my salary, while having the flexibility to work on my own schedule from anywhere.

And it’s not just about money and flexibility. I’m working on projects that can positively impact many more people. I get to experiment with exciting new machine learning tools. And above all, I love what I’m doing.

The problem: it’s pretty damn hard to learn these skills (even if people may tell you otherwise). Especially if you have a full-time job or a child (I had both 👶 ).

Here’s a six-step roadmap to become an MVP data scientist (or know just enough to be dangerous).

(Note: this is an updated version of an article I wrote in 2019. In short, the field has moved and my opinion on how best to learn this has changed.)

What does it mean to do data science?

Data science is about using data to answer questions and to make predictions.

More and more information about the world is stored as data, hence the need (and the power) of data scientists.

Doing data science can be broken into:

- Finding or creating data

- Preparing data for analysis

- Doing the analysis and interpreting the results

- (if relevant) creating a model for future use

This typically involves executing a fairly standard “data science” pipeline, which I have written about previously. (This centres around the popular “CRISP-DM” pipeline) The ability to execute this pipeline can be divided into six levels of competence:

The six stages of data science competence

Stage 1: Understanding core programming principles: knowing what’s a variable, what’s a function, how is data stored and more

Stage 2: Managing the data science environment: being able to set up a jupyter notebook, import the required libraries, load data and look at it, visualise and understand it.

Stage 3: Building a simple model: being able to use data to fit a model, such as a regression model or simple classifier

Stage 4: Doing the data science pipeline: for a simple data science problem, being able to define the data science task, select an appropriate model, train it, interpret the results and draw initial conclusions.

Stage 5: Adapting the data science pipeline: for more complex data science problems, being able to adapt the typical pipeline to more challenging situations and “answer your own questions” as potential problems arise.

Stage 6: Developing expertise: optimising your own workflow to save time, developing your own style as a data scientist

“Becoming a data scientist” involves progressing up these rungs. Below I’ll share steps for progressing through each stage.

So… where does AI and machine learning fit in?

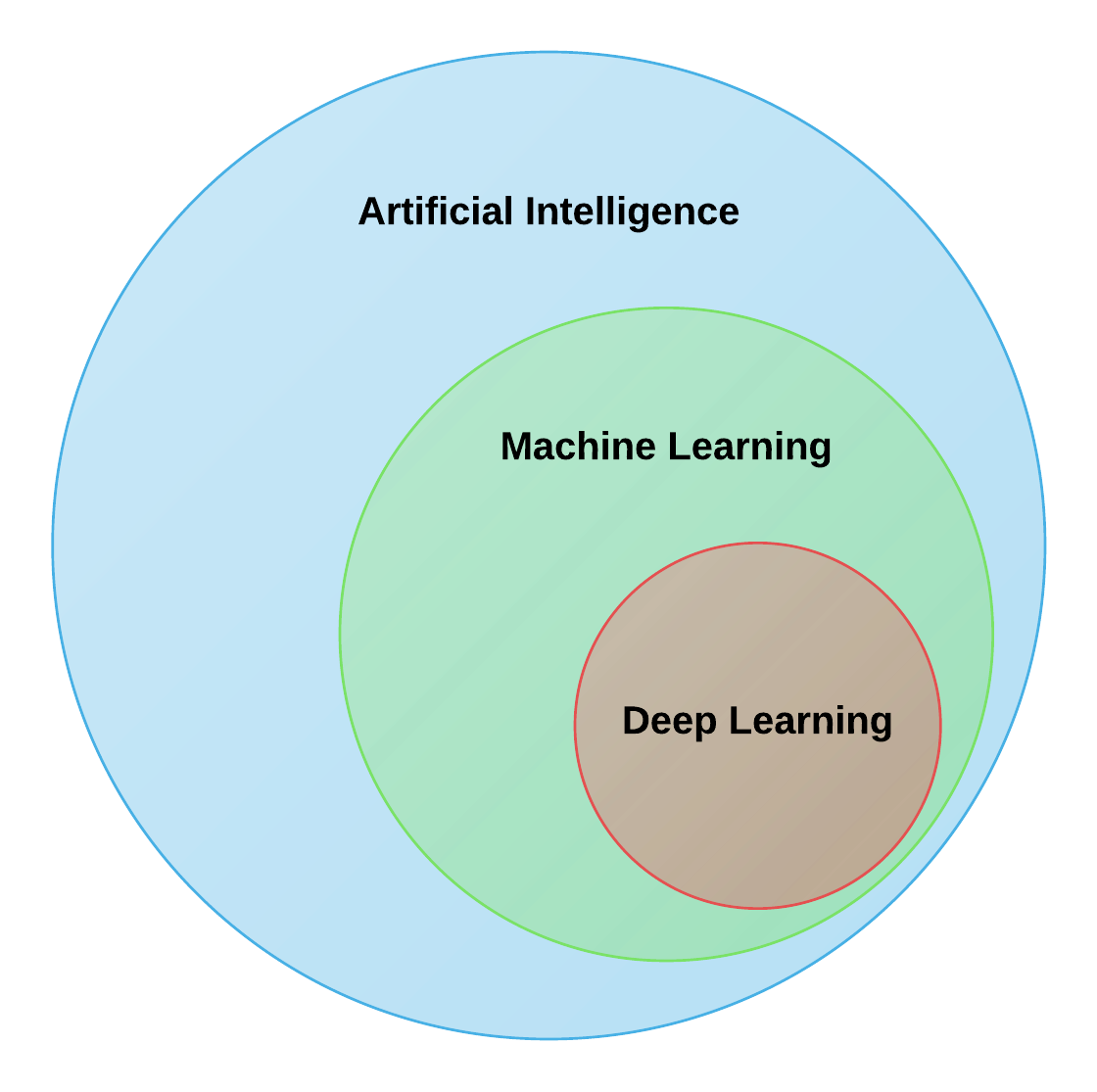

“Data science” encompasses the wider area of using data to answer questions and to make predictions. Machine learning techniques are one set of the tools that we can use. They’re used pretty commonly, although sometimes “boring” statistical techniques are more appropriate.

There’s a sub-area of machine learning called “deep learning” which involves training neural networks. They’re particularly good for certain types of data, like images and text data, and require large volumes of data to train.

These can also be used as part of the data science pipeline. For example, you might want to classify some X-rays as being normal or not. However, for the majority of real-world use cases, only “simple” data science is required.

Incorporating deep learning also represents an additional level of complexity on top of the foundational data science pipeline. I’d recommend building base data science competence (stage 4 or above) before looking to incorporate it.

There are also areas of AI and machine learning that don’t fit into this data science paradigm. For example, generative AI has gained a lot of interest recently, following stable diffusion, chatGPT and other advancements. Utilising these technologies involves a different skillset, for example figuring out the right “prompts” to give the model (aka prompt engineering) and also building software around the models.

Can’t I just use no-code/low-code tools?

An implicit promise of no-code tools is that you can do data science without knowing how to code. I disagree.

I don’t think you should learn how to use these tools until after you learn to code.

Firstly, these tools have limitations, which you’ll bump into pretty quickly. For example, if you data isn’t formatted in a certain way, the tool might not be able to process it properly.

Secondly, many of these tools are designed for companies, not individuals. This makes the pricing prohibitive if you’re a solo developer building your skillset.

And finally, to use the best tools you’ll still need to write some code. For example, PyCaret is a popular library which lets you do a whole data science pipeline in 5-10 lines of code. But you still need to know how to set up your environment, load your data and execute those 5-10 lines of code.

The key point is this: Learning to code helps you use no-/low-code tools. Learning no-code tools won’t help you to code.

Once you can code, you’ll be able to use no-/low-code tools for quick iteration and testing - and you’ll be better at using them given the understanding you’ve built.

And in many ways, the popular “coding” tools today are already pretty low-code compared to what people used to code 10 or so years ago. Back then, you’d have to code a neural network from scratch. Now, you can just import a “neural network” function from a library like scikit-learn and get going.

So in summary: yes, you should still learn to code.

How to Achieve Each Level of Competence

Stage 1: Learning core programming principles

When I first wrote about learning data science, I recommended starting with common machine learning algorithms and the maths behind them.

My opinion has changed. I think you should learn to code straight away.

The technical details behind ML algorithms are increasingly being ‘abstracted away’. Algorithms you used to hand-code 10 years ago can be imported and run with three lines-of-code today. Deep learning removed a lot of need to manually prepare data for analysis. And NLP models are increasingly able to solve multiple tasks (just based on changes in their text prompt), rather than being tailored to a specific task.

Using these models (outside of the simple ‘playground’ environments) requires you to write small amounts of code: to load the models, tweak the data as appropriate and look at the output. So these basic programming skills are a fundamental requirement.

Of course, understanding the algorithms you’re using is still helpful. I just don’t think it’s the first thing you should do. You could train a pretty good random forest classifier, for example, without having a clue how random forest actually works.

In terms of language, you can’t really go wrong with Python. It has huge adoption across industry and a great selection of packages to enable you to do most tasks.

The core principles are the same across most languages though: data types, variables, functions, etc. (My first programming course was Javascript, and helped for Python just fine.)

In general, I think you should Learn To Code Through Projects, Not Courses, but ultimately you need to work through a course to get the ball rolling.

The depth at which you learn programming will ultimately depend on the type of data scientist you’re going to become: Will you mostly do standalone analysis (in a Jupyter notebook) or will you be building, deploying and monitoring ML models? Given that you won’t know this yet, I’d recommend doing a few courses and exercises (suggestions below) and re-visiting this once you’re at competence stage 5.

Courses and exercises

- I recommend using a free Python course like this one from freeCodeCamp

- Harvard have a great course called CS50, although it goes beyond what you need to know at this stage. Worth considering if you want to build a wider base of understanding.

- Here’s an exercise on core Python Programming principles.

- And here’s an exercise applying those principles to making a medical calculator

Stage 2: Learning to load and analyse data

Once you understand the core principles, the next step is to be able to apply them to some real-world data.

To actually do something useful, you need to get comfortable outside the confines of courses.

I’m including this as its own stage, as I actually think this is pretty tricky. There’s a bunch of steps required to set an environment, load in data, load in the packages you need, etc - and a bunch of confusing errors you can run into along the way.

My top recommendations at this step would be (1) perseverance and (2) tap into technical friends if you have them.

For the typical data science pipeline, you’ll do most of your heavy lifting in a jupyter notebook. It makes it easy to visualise and interact with your data. At some point, you’ll want to start generalising code into python (.py) files and importing them into your notebook - but only worry about this once you have more experience.

So the main things to do at this stage are:

- install jupyter notebook

- learn how to install packages (like pandas, numpy, scikit-learn) and import these into your notebook

- learn how to download data and import these into your notebook (via pandas)

I’d recommend following some tutorials - and a lot of Googling (which includes copying + pasting error messages that you may get).

It would also be helpful at this stage to establish some good practices. If you can, learn to use an environment manager like conda or venv (check out this article and this one) - it’ll put you in great stead for the future.

Sometimes you’ll get the environment working, but then run into a new problem when you e.g. change computers or tweak your settings. This is normal, and over time you’ll accumulate experience of how to solve these common problems.

Courses and exercises

- Python for Data Science courses can also be helpful at this stage. freeCodeCamp have this one.

- I wrote this exercise about getting setting up with Jupyter Notebooks

Stage 3: Building a simple model

Now comes the fun stuff. Here, you load your data and do a full “data science pipeline”, which broadly consists of (1) preparing (“preprocessing”) the data, (2) training a model and (3) assessing the model performance.

For this, you’ll need a basic understanding of what each of these steps involve. The quickest way to get this understanding is to work through a few tutorials (YouTube walk-throughs are great for this - links below).

Once you get the idea, pick a dataset and code your own pipeline. You can borrow code snippets from the different tutorials you’ve watched.

At this stage, I’d just focus on getting it to work. We’ll develop a better understanding in the next stage.

Try and find an interesting dataset to make this fun. I’ve collated a list of open-source health datasets to work with (accessible here). Alternatively, look for datasets on Kaggle, which often also have demo notebooks to act as a helpful template.

The easiest task will be either a regression of classification problem using algorithms recommended on scikit-learn.

If you can end up with a fitted model and a broad understanding of how it’s performing, then it’s a success.

Courses and exercises

- I’ve written about the core data science pipeline here

- And I’ve made a bunch of exercises and walkthroughs (from beginner to advanced). Links to the code, YouTube videos and long-form articles are available in this Coding For Medicine repository.

Stage 4: Doing the data science pipeline

This is the point at which I would now recommend fleshing out your understanding of the theory. You’ve got the core technical skills required to execute, so now you want to build the ability to make the right decisions around what to execute.

Of course, data science and machine learning is a huge area, and life is finite, so we need to aim for the appropriate depth of understanding for what we’re trying to do.

There are certain must-knows, which include:

- Types of task: supervised vs unsupervised, regression vs classification

- Performance metrics for classification (AUC, F1 score) and regression (MSE, RMSE, R-squared score)

- Underfitting and overfitting: how to diagnose them and how to respond

- Popular algorithms for each task (e.g. logistic regression, support vector machines, k-nearest neighbours, random forest, etc for classification). A broad understanding of how they work, what sorts of data they work best on, and their complexity (and therefore risk of underfitting / overfitting)

You’re never really “done” with this, as you’ll always be improving. But I would consider this stage “completed” once you’re fairly confident at:

- coming across a new dataset

- identifying the type of task, and thus the appropriate preprocessing required and potential algorithms

- implementing those algorithms and using the results to update your approach

But there may still be times when you come across something new and you’re not sure how you would handle it - that’s what you’ll learn to overcome in the next stage.

Courses and exercises

- I outline the key theory (through a healthcare lens) in this video series

- The core data science pipeline is also relevant here

- The Coding For Medicine repository has a lot of relevant exercises for this stage too. I’d recommend the intermediate exercises, like diagnosing breast cancer and predicting hospital non-attendance.

Stage 5: Adapting the data science pipeline and “answering your own questions”

At this stage, you’re able to confidently “answer your own questions” when you come to them (with or without the help of Google).

The route to get here is ultimately to gain more experience, and to learn from supervision during that experience. You’ll want to internalise the way of thinking and solving problems that someone more senior has.

I’d say you hit this point broadly after somewhere between 3 and 10 “serious” projects (of at least a month). So you’re looking at atleast three-to-six months of work.

| This is the point at which you can start to function as a broadly-standalone data scientist and work autonomously on projects in academia or in industry. There’s an option to start directly monetising your skills. <!– (see my [A guide to monetising data science skills | guide to monetising data science skills] if that’s part of your plan). –> |

This is also the point at which you can really start to have fun - by e.g. finding data on the internet, playing around with it, and sharing your findings. (At some point, it’s probably worth learning SQL to help you query data from certain databases.)

Courses and exercises

No specific courses now. The main thing is to find projects you could work on under supervision. Are there projects going on at your current workplace? Or in your wider industry? If not, could you get a job that offers this? Also, competitions like Kaggle could potentially be helpful, if you can find or create a team.

Stage 6: Going pro

If you keep doing data science in a serious way, you’ll start to optimise your workflow to save time, and to discover your own personal style of doing data science.

This is also the point at which you can start moving more into deep learning (when it’s appropriate). The “basic” data science pipeline from steps 1-5 is a great foundation for this.

Like stage 5, this ultimately comes from more hands-on experience.

Can I really do this alongside a full-time job?

If you’re asking yourself this question, here are four suggestions:

(1) Be specific about your aims

Data science and machine learning is hard. It may feel intimidating to learn it alongside other full-time commitments.

It becomes less intimidating, though, when you focus the scope. Rather than “I want to learn machine learning”, you could say “I want to be able to run a data science pipeline, with supervision” (ie. Stage 4). I hope this article provides the framework for doing so.

(2) Understand your why

It’s important to have a clear why. On the days when you get home from work and feel tired, you’ll need a reason to keep going. Perhaps you’re not enjoying your current job and have an alternative path in mind. Perhaps you want to build skills that help in your current job. In my case, I knew I wanted the self-sufficiency to build cool products and analyse interesting data based on whatever ideas came to my mind. If you’re medical too, I strongly believe more clinicians should learn to code and do data science.

(3) Consider making more time - and take Little Bets

Ultimately, it’s true that you can make faster progress when you’re devoting more time. So if you’re serious about building your skills, you could consider how to change your current job or lifestyle to create more time. (In my case, I took some time out of medical training to do data science full-time.)

But knowing whether you’re serious can be tricky. What if you don’t actually enjoy it as much as you thought? Taking “Little Bets” can be helpful before making any major life changes. For example, one “little bet” could be committing to 2 months of part-time self-study to get to Stage 3. (I had more than a year of part-time experience before I committed to going full-time.)

(4) Enjoy the ride

It may sound trite, but it’s also much easier to find time if you’ve having fun. Try and find data and answer a question you’re genuinely curious about. Follow your inclinations, not just what some course (or a guide like this) recommends.

Go forth and create

The career paths for incorporating data science skills are not always yet well-defined. Industries are still adapting to the shift towards data. In medicine, for example, there’s discussion around future roles like “clinical informaticians”, but they’re not yet formalised.

Proactively building these skills now will put you at the forefront, so that when such opportunities inevitably arise, you’ll be best-placed to take them.

If you want to make an impact on the world and have an exciting life, you need to do things differently - and building data science skills can be a vehicle for doing so.

Thank you to Mustafa Sultan and Mustafa Ghafouri for their feedback on this article.

Related

- In this article I share my experiences transitioning to a full-time data scientist from being a doctor, and tips for doing so.

- The Part Time Creator Manifesto by Shawn Wang

Comments powered by Disqus.